General Information

- General Information

- Associated Anatomy & Physiology

- Associated Histology

- Epidemiology

- Etiology, Pathogenesis & Pathology

- Pathophysiology

- Diagnosis

- Evaluation

- Special Types & Phenotypes of Asthma

- Asthma Mimics

- Diseases Associated with Asthma

- Exacerbation

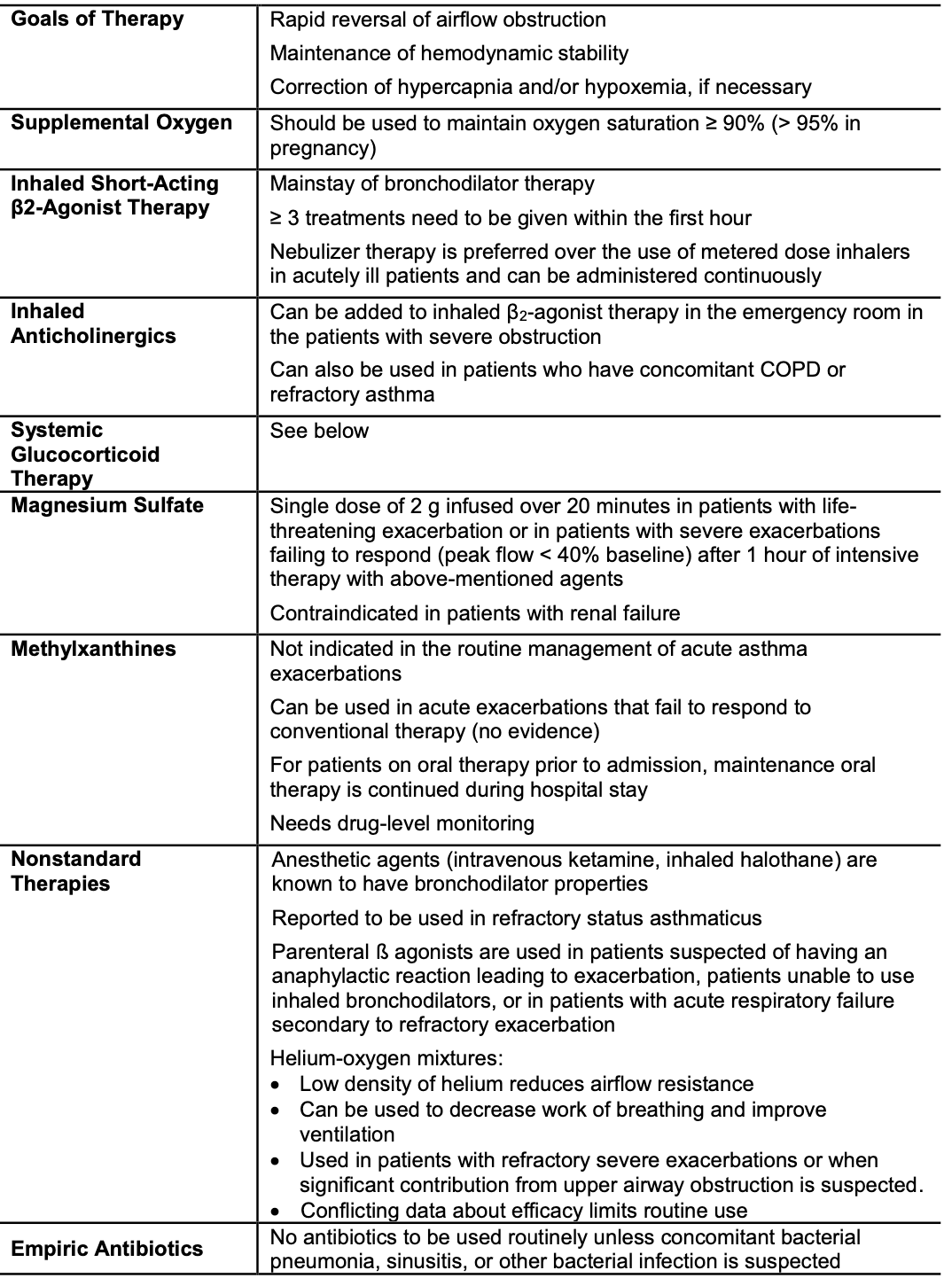

- Management

- Definition: heterogenous & chronic inflammatory disorder of airways characterized by hyperreactivity (hyperresponsiveness) of the airways causing airway narrowing due to exaggerated response of airway smooth muscle contraction (due to a wide variety of stimuli) leading to reversible episodes of bronchoconstriction and therefore variable expiratory airflow limitation (symptoms vary in intensity over time)

- hyperresponsiveness of airways due to exaggerated smooth muscle contraction —> bronchoconstriction that is reversible —> variable expiratory airflow limitation

- Exacerbations happen interspersed between intervals of diminished symptoms or symptom-free period

Associated Anatomy & Physiology

Associated Histology

Epidemiology

- Highest prevalence and severity in children (9.3%), low socioeconomic level (12.4%), and specific minorities (Puerto Ricans [18.8%] & black, non-Hispanic Americans [11.9%])

- Most prevalent chronic respiratory disease worldwide

- Estimated global prevalence of 358 million (2015)

- 25 million Americans have current Asthma

- US Prevalence 7.8% (2019)

- Increased over time -- 7.3% in 2001

- Prevalence by Sex

- Overall F > M except in childhood where M > F

- Prevalence by race/ethnicity

- Overall: PR > Black > White > Hispanic > Mexican

- Adults: PR > Black > White > Hispanic > Mexican

- Children: Black > PR > White & Hispanic > Mexican

- US Prevalence 7.8% (2019)

- 250K asthma-related deaths each year worldwide

- In US, 14.4 per 1 mil (1980) → 21.9 per 1 mil (1995) → 17.2 per 1 mil (1999) → 15 per 1 mil (2009)

- Disproportionately affects blacks (38.7 per 1 mil) and those of PR heritage (40.1 per 1 mil)

- Unknown the real cause of this

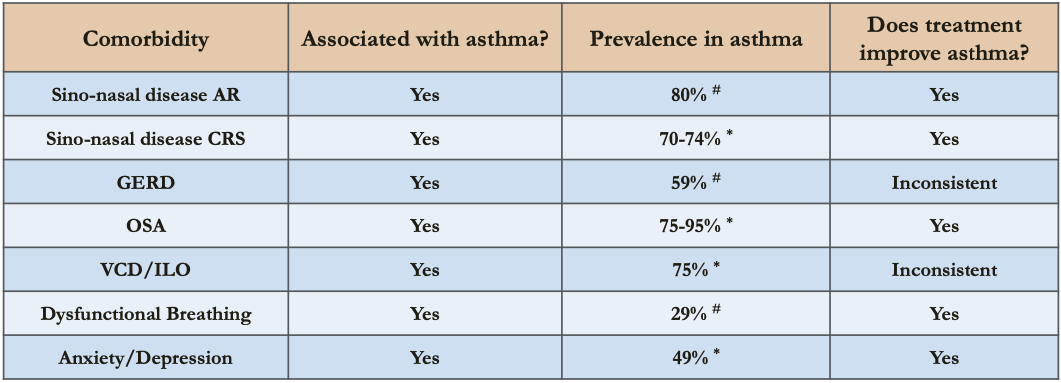

- Associated Conditions

- Comorbidities which may aggravate asthma

- Allergic rhinitis

- Sinusitis

- GERD

- Patients w/ asthma at increased risk of developing GERD — CASE-CONTROL STUDY: Chest 2005 Jul;128(1):85

- GERD and Asthma may be associated in adults — SYSTEMATIC REVIEW: Gut 2007 Dec;56(12):1654

- GERD common in difficult-to-control asthma (found in 75% of 52 patients) but GERD treatment may not improve asthma — Chest 2005 Apr;127(4):1227

- Nasal polyps

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- Obesity

- Depression and Anxiety

- Depression and anxiety may be more common in adolescents with asthma — SYSTEMATIC REVIEW: Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012 Dec;23(8):707

- Asthma associated with suicide attempts — CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY: Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008 May;100(5):439

- Comorbidities which may aggravate asthma

Etiology, Pathogenesis & Pathology

Biology

Genetics

- Strongest risk factor = family history of allergy — estimates of heritability range from 35-70% (higher for early-onset asthma)

- increased risk of developing allergic rhinitis

- increased risk of developing asthma

- Serum IgE correlates strongly with bronchial hyperresponsiveness

- Association with gene variants at Chromosome 17q21 locus — a/w childhood asthma not adult-onset; genes GSDMB & ORMDL3 -- specific to childhood onset disease

- Polymorphism in

- IL-4, IL-13 genes -- allergies, IgE

- CD14 and TLR genes -- farming and endotoxin exposure

- TGF-β1, MCP-1 -- fibrosis/remodeling

- Gene for the β chain of the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FCER1-β) -- allergies

- β-receptor (Arg/Arg) and glucocorticoid polymorphism determine heterogeneity in treatment response → mutation causes downregulation of β2 receptors decreasing response to treatment

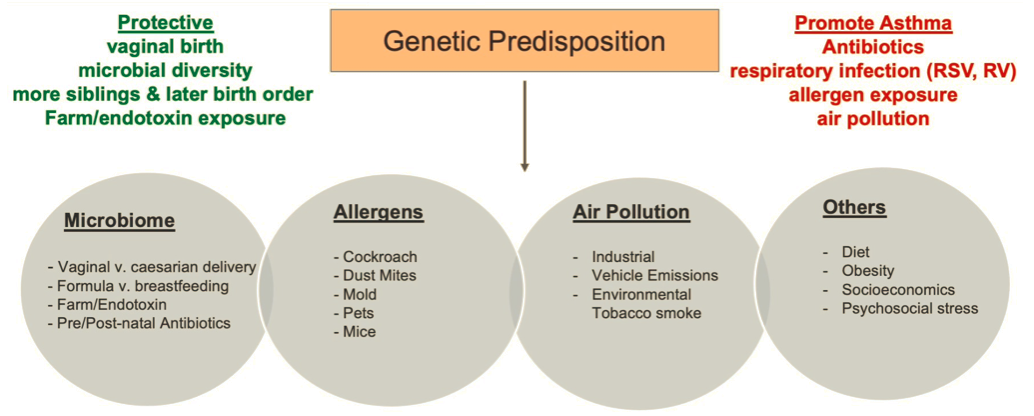

Risk Factors

- Strongest = Family history (above)

- Other risk factors

- Specific allergens: House dust mites, dog and cat dander, cockroach — controlling these is part of the treatment of asthma

- Early life infections

- Hygiene hypothesis —protective effect

- rise in allergies in children is an unintended consequence of the success of domestic hygiene in reducing the rate of infections or exposure to bacterial products in early childhood

- essentially due to the improved hygiene you have less exposure to allergens and bacteria (exposure to this is supposed to promote Th1 immunity (cellular defense) → which is responsible for blunting Th2 immunity)

- Increase risk for wheezing illnesses and asthma over time as a result of viral respiratory infections (RSV and Rhinovirus)

- exposure early in life leads to asthma

- unclear whether its a direct causation or whether it unmasks a predisposition to predominant Th2 like responses

- if those children develop lower respiratory infections due to RSV and Rhinovirus they are at 3-4-fold risk of subsequent wheezing during early school years

- Early wheezing = age <3; persistent wheezing = present at age 6

- Early wheezing — a/w RSV and Rhinovirus → can become persistent (this is due to atopy) or can be transient (this is due to maternal smoking)

- Late-onset wheezing — starts at age 6 — also due to atopy

- children who lived in farms had a lower prevalence

- Hygiene hypothesis —protective effect

- Atypical Bacterial Infections

- Mycoplasma and Chlamydia pneumoniae

- infect the airway epithelium → stimulate local inflammatory reactions

- more common in the airway of patients with chronic stable asthma

- a/w increase in tissue mast cells

- Lower airway biospecimens from asthmatics show abnormalities in the composition of bacterial microbiota, especially Proteobacteria (which include H. influenzae, Pseudomonas, Neisseria, Burkholderia species, and Enterobacteriaceae species.

- Notably, Proteobacterial species promote neutrophilic inflammation, and there is now great interest in whether specific microbial pathogens drive specific subtypes of asthma (such as neutrophilic asthma)

- Mycoplasma and Chlamydia pneumoniae

- Intrauterine exposures

- growth rates — both high and low

- dietary vitamins D and E deficiency; vitamin D plays a role in immunoregulation

- exposure to microbial products

- parental smoking

- parental stress

- Perinatal Risk Factors

- prematurity

- chorioamnionitis

- Early Childhood Risk Factors

- shorter breastfeeding period

- obesity

- absence of older siblings or daycare attendance (i.e. exposure to other children)

- antibiotic use

- acetaminophen use (especially when given in 1st year of life; ? dose dependent)

- Bacteroides fragilis colonization at age 3 weeks is a/w increased risk of asthma

- Upper airway colonization in infants by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis predicts later development of asthma

- Air pollution

- no data to suggest that air pollution can contribute to the development of asthma

- however increased prevalence in those with proximity to heavy automobile traffic due to exposure of particulate matter and NO2

- Occupational exposures

- accounts for 17% of adult-onset asthma

- can be

- immunologically mediated sensitization to occupational agents — sensitizer-induced occupational asthma

- exposure to high concentrations of irritant compounds — irritant-induced occupational asthma

Natural History

- Atopic/Allergic March

- pattern of atopic disease during infancy and childhood that begins with atopic dermatitis or eczema in the 1st year of life (+/- food allergy) then progresses to development of rhinoconjunctivitis then asthma later in life

- Teenage Years

- starting in puberty, asthma changes from male predominance to female predominance (which continues into adulthood)

- ? hormonal component

- Remission

- R/F a/w greater likelihood of persistence into adulthood — sensitization to house dust mites, lower FEV₁, airway hyperresponsiveness, female gender, and smoking at the age of 21

- data to suggest that the inflammatory response really never goes away even in patients in "remission" (elevated Fraction of NO, bronchial biopsy show eosinophils, T cells, mast cells, and increased subepithelial fibrosis)

- Progressive Airflow Obstruction

- Deposition of collagen and growth of vessels, smooth muscle, secretory cells and glands → progressive narrowing of airways in chronic asthma

- Adulthood

- many had symptoms as a child

- can be de novo — usually after an acute URI

- Elderly

- if asthma presents as an adult it will continue later in life

- elderly patients more likely to have fixed airway obstruction compared to children

Pathogenesis

Mechanisms of Asthma

.png)

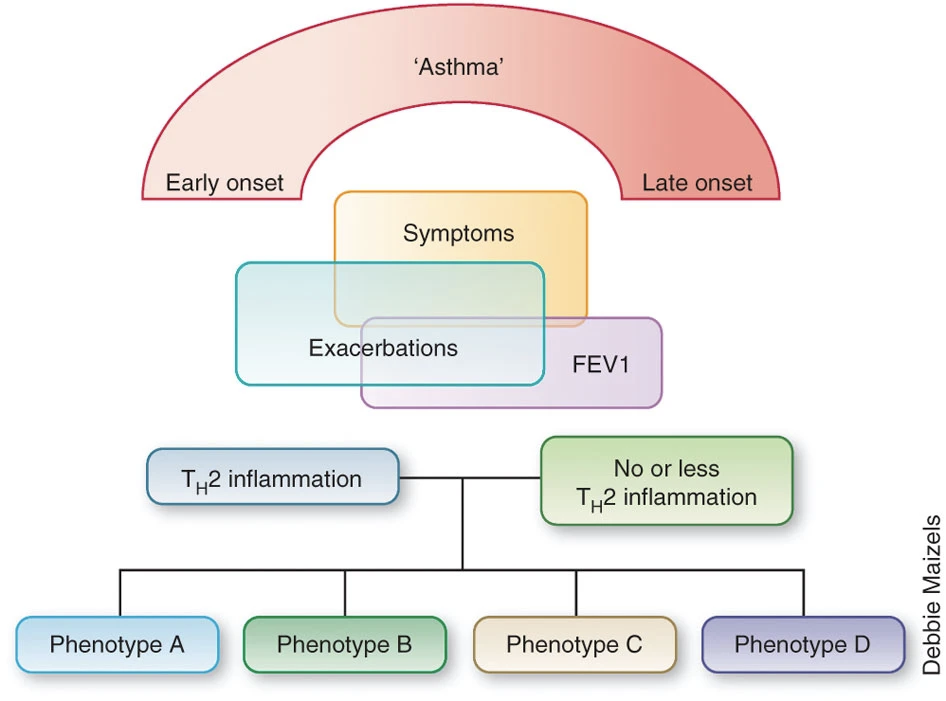

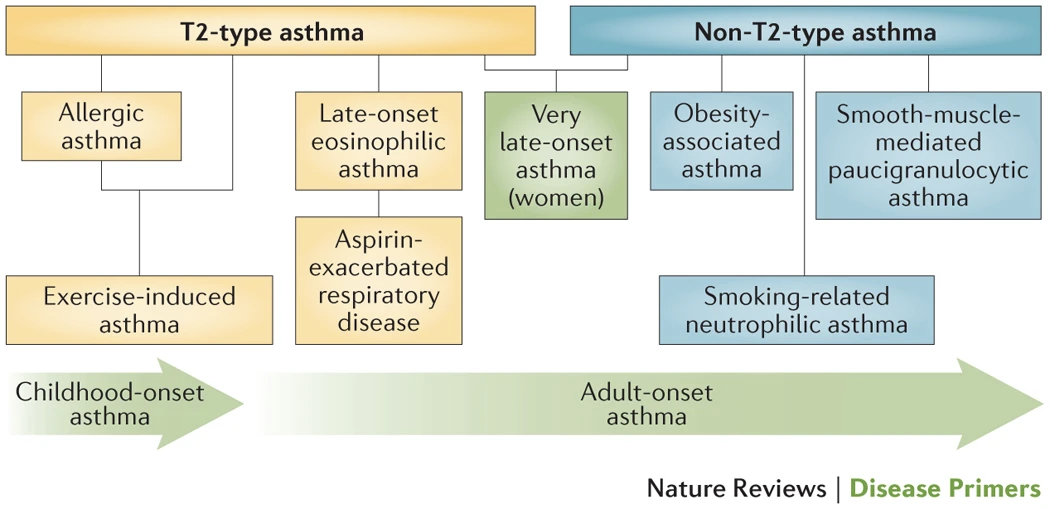

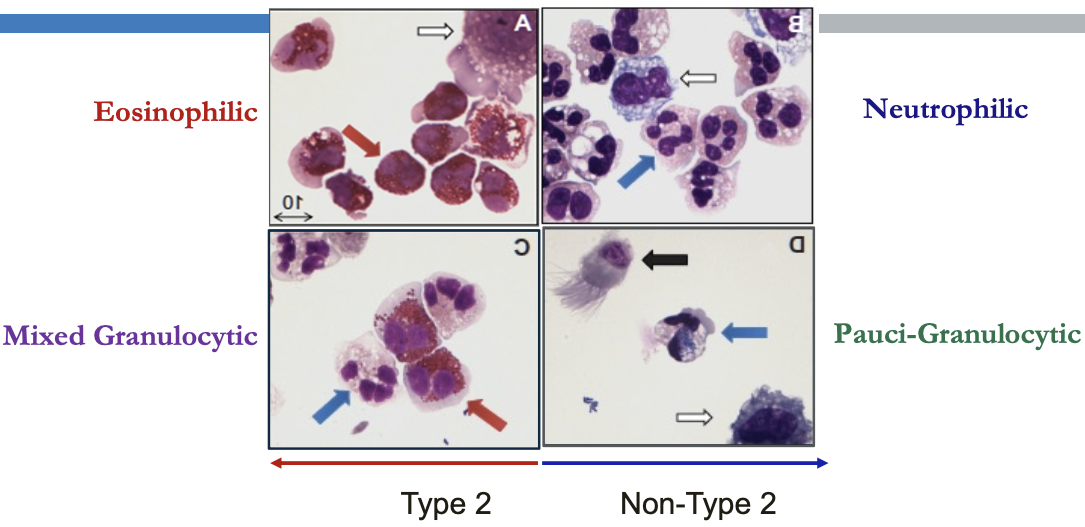

Phenotypes

- What we call asthma may not represent a single disease process but rather the summation of a number of pathogenetic pathways (endotypes) that have differences in expression (phenotype) w/ common features being airway inflammation and episodic bronchoconstriction

- (Wenzel Nature Medicine 2012)

- (Holgate Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015)

- Phenotype — observable characteristics that result from a combination of hereditary and environmental influences.

- Endotype — distinct mechanistic/molecular pathway leading to a certain phenotype

- Biomarker — a measurable indicator of presence or severity of a disease state

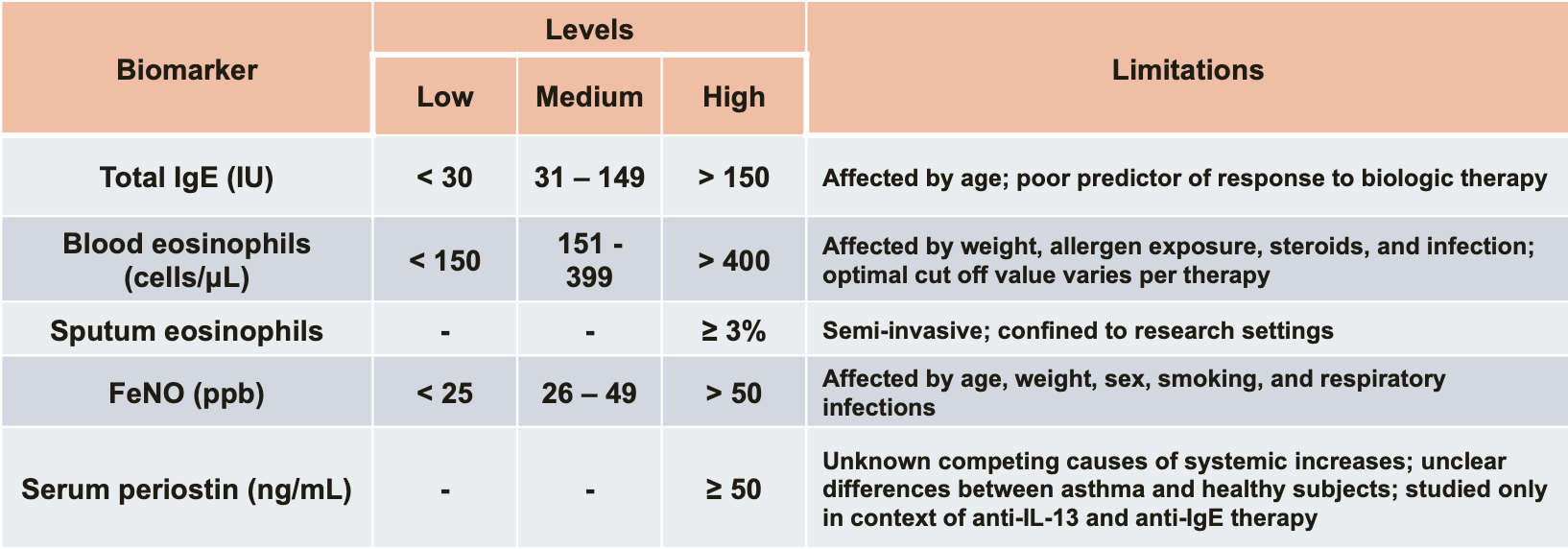

- Comparison of Type 2 Biomarkers in Asthma

(Peters MC, et al. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16(10):71)

(Peters MC, et al. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16(10):71)

.png)

Airway Inflammation in Asthma

- Biologics: Targets and Therapy 2013:199

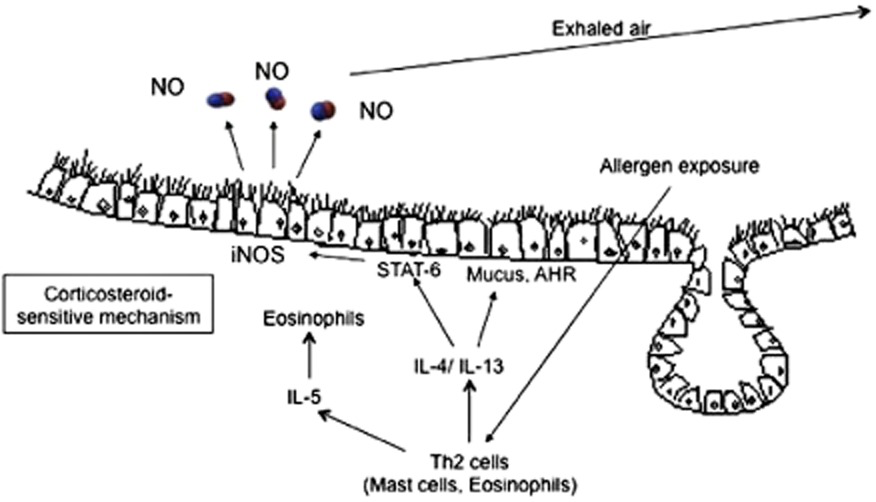

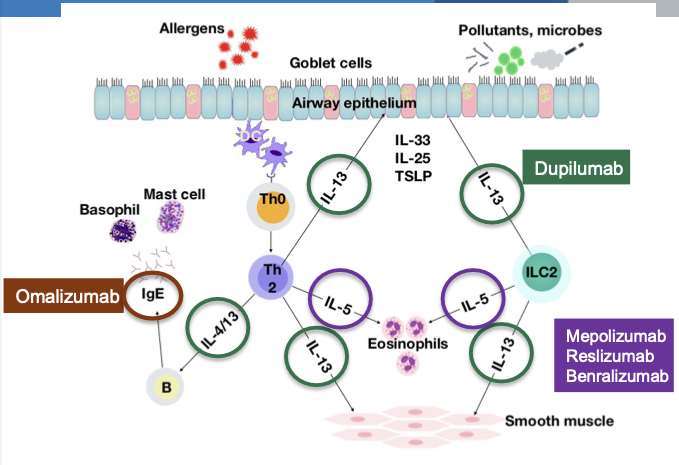

Type 2 (Th2-High) Immune Responses in Asthma

- Eosinophilic inflammation may be allergic or non-allergic

- Cytokines in Type 2 Asthma

- Epithelial cytokines (alarmins) - TSLP, IL-33, IL-25

- IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 -- produced by helper T cells, basophils, mast cells, & eosinophils

- IL-5 -- differentiation and maturation of eosinophils

- IL-13 -- recruitment of eosinophils into the airway, mucus hypersecretion, airway hyperresponsiveness

- IL-4 -- IgE production by B cells (class switching)

- IgE -- activates mast cells & basophils to produce leukotrienes that recruit and activate eosinophils

- Th2-High

- increased expression of IL-13 & IL-5

- exaggerated airway hyperresponsiveness — methacholine

- higher serum IgE levels

- higher eosinophils (blood and BAL eosinophilia) (>3%)

- increased thickness of fibrosis below the airway epithelial BM

- Increased MUC5AC/MUC5B ratio → increased expression in goblet cells

- Increased number of intra-epithelial mast cells

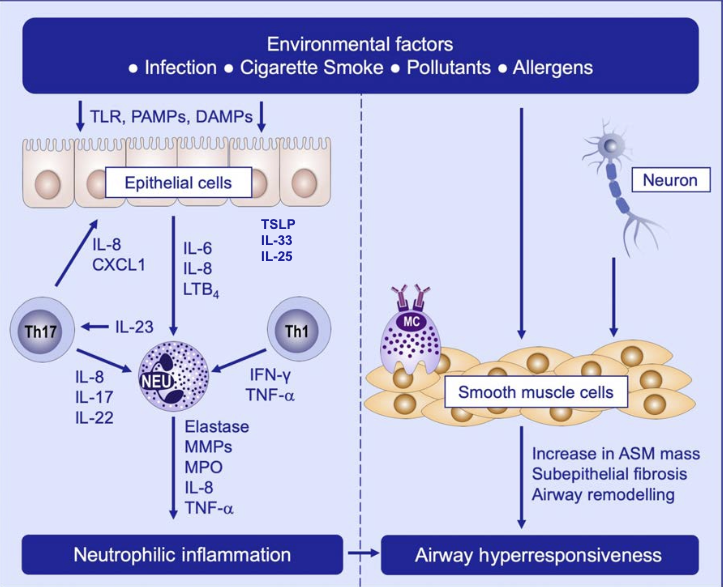

Non-Type 2 (Th2-Low) Mechanisms

- Airway inflammation does not play a dominant role in clinical manifestations in Th2-low rather a result of abnormal airway smooth muscle response (contraction by histamine and ACh)

- Sze & Nair. Allergy 2019

- Driven by Th1 & Th17 → airflow obstruction & exacerbation

- Th1

- IFN-γ dependent airway hyperresponsiveness → corticosteroid resistance

- Th17

- IL-17, IL-21, IL-22, IL-8 but not IFN-γ or IL-4

- most parenchymal cells (including airway epithelial cells) express receptors for Th17 cytokines → IL-17 → production of pro-inflammatory factors (IL-16, IL-1, TNF-α & IL-8 (which attracts neutrophils))

- IL-17 → increases epithelial production of secreted mucins

- Th17 → steroid resistance

- Th1

Neutrophilic Asthma

- Persistent inflammation

- Increased disease severity

- Airway remodeling

- Corticosteroid refractoriness

Paucigranulocytic asthma

- Most common phenotype in stable asthma

- 20% can be severe/refractory

Mechanisms of Asthma Exacerbation

- exacerbations represents acute on chronic worsening of airflow obstruction due to worsening airway smooth muscle contraction, airway wall edema, and luminal obstruction with mucus

- repeated airway remodeling → susceptibility to acute reductions in airflow

- changes in epithelium → increase mucin stores → mucus hypersecretion → more hyperreactive

- changes in airway smooth muscle → concentric smooth muscle contraction → more hyperreactive

- changes in blood vessels → increased permeability → vulnerable to exaggerated airway responses to inhaled environmental insults → worsening mucosal edema → more hyperreactive

Pathology

- structural changes in epithelium and submucosa

- Edema (from Nitric Oxide) and cellular infiltrates within the bronchial wall, especially with eosinophils and lymphocytes

- Epithelial Changes

- Main Changes

- Goblet Cell Metaplasia & Hyperplasia

- increasing amount of gel-forming mucins that are stored in the airway epithelium

- Epithelial damage, with a "fragile" appearance of the epithelium and detachment of surface epithelial cells from basal cells

- Goblet Cell Metaplasia & Hyperplasia

- Less Common Changes

- Desquamation — acute severe asthma exacerbation (not chronic stable asthma)

- Squamous metaplasia — usually seen in smoking-related lung injury not asthma

- Main Changes

- Airway Mucus Changes

- Higher mucin concentration than normal

- MUC5AC upregulation in epithelial cells and MUC5B downregulation

- Presence of albumin — prominent protein in asthma

- reflects increased vascular permeability (especially in acute exacerbations)

- albumin + other proteins + mucin → increase mucus viscosity

- Higher mucin concentration than normal

-

Subepithelial Fibrosis

- Increased amounts of types I, III, and V collagen + fibronectin and tenascin → deposited immediately underneath the epithelium (which means underneath the basement membrane)

- Recall basement membrane is made up of collage IV and laminin so this is underneath the basement membrane layer

- source of these collagens are the epithelial cells and myofibroblasts (which are increased in number in asthma)

- more prominent in Type 2 Eosinophilic asthma

- Due to the stiffness of the matrix, it causes persistent activation of overlying epithelial cells and smooth muscle cells → bronchoconstriction

- Airway Smooth Muscle Cells

- Mild-moderate asthma — hyperplasia of airway smooth muscle

- Severe asthma — hypertrophy + hyperplasia of airway smooth muscle

- increased shortening of airway smooth muscle → affects elastance

- Blood vessels

- Quantity and size increases

- Increase in vascular volume → mucosal swelling → narrowing of airway lumen

- all due to increased permeability from vasodilation

- Airway Pathology in Fatal Cases of Asthma

- severe concentric smooth muscle contractions + extensive mucus plugging → segmental and subsegmental lung collapse

- greater airway wall thickening, airway smooth muscle hypertrophy (leads to bumps on the airway) and submucosal gland hypertrophy

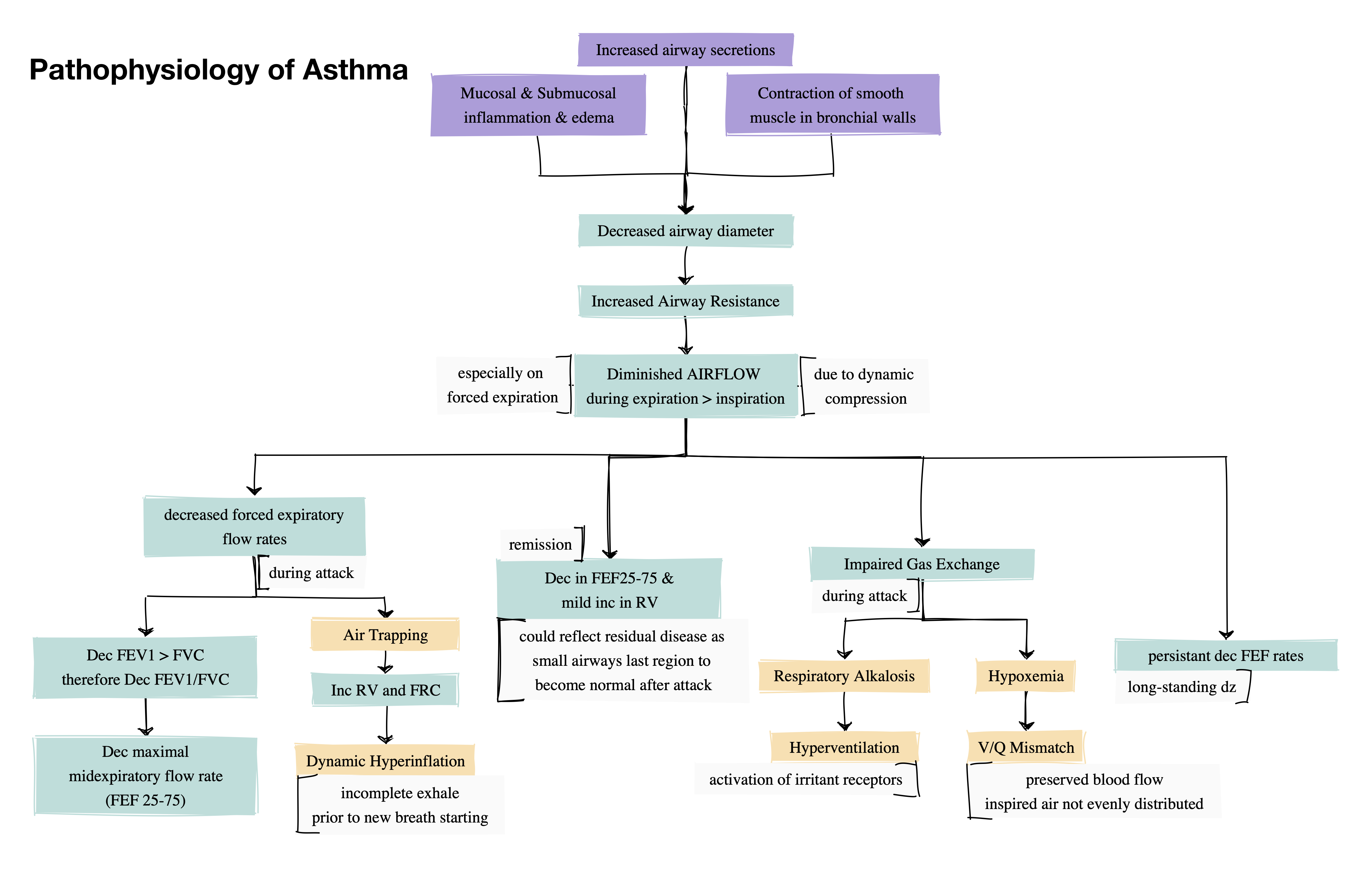

Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

Evaluation

Pattern of Symptoms

-

Symptoms

- Recurrent pattern of symptoms

- More than one symptom

- Worse at night or early morning

- Vary over time and in intensity

- Identifiable triggers

Relevant History

- Childhood asthma or atopy

- Family history of asthma or allergy

- Occupational or environmental exposures

- Medications

- Timing of last asthma dose

- Use of ACE-I (angioedema or chronic cough)

- ASA/NSAIDs

- β blockers (including eye drops)

- cardioselective β blockers — cardioselective β blockers do not appear to produce clinically significant adverse respiratory effects in patients with mild-to-moderate reversible airway disease — COCHRANE REVIEW: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(4):CD002992

- without intrinsic sympathomimetic activity — atenolol, bisprolol, practolol, metoprolol

- with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity — acebutolol, celiprolol, xamoterol

- topical β blockers — both cardioselective and noncardioselective topical β blocker antiglaucoma drugs may be associated with increased number of hospital days in patients with obstructive pulmonary disease — COHORT STUDY: Curr Eye Res 2009 Jul;34(7):517

- switch to selective β blocker such as betaxolol as a temporizing measure until definitive therapy (eye surgery) is attempted

- Topical β adrenergic blockers gain access to the systemic circulation through the lacrimal glands and then may be absorbed through the nasal mucosa or through conjunctival vessels

- cardioselective β blockers — cardioselective β blockers do not appear to produce clinically significant adverse respiratory effects in patients with mild-to-moderate reversible airway disease — COCHRANE REVIEW: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(4):CD002992

Physical Exam

- Often normal

- Expiratory wheeze

- may only be heard on forced exhalation

- Wheeze may be absent in acute severe asthma

- 'Silent Chest'

- Nasal polyps/rhinitis

- Skin -- dermatitis, eczema

Testing

Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR) variability

- PEFR variability during the day

-

10% variability in adults

- performed twice daily over two weeks

-

Document Airflow limitation on spirometry

- Reduced FEV₁/FVC

- FEF 25-75

- midexpiratory flow

- measured at lower lung volumes than FEV₁ → more sensitive to obstruction in small airways → can predict airway hyperresponsiveness

Confirm Bronchodilator reversibility

- Improvement in FEV₁ >200 mL AND 12%

Variability in FEV₁ between visits or after treatment

- Change in FEV₁ >200 mL AND 12%

- In a patient with respiratory symptoms, the more variation in lung function that is seen, more likely diagnosis of asthma

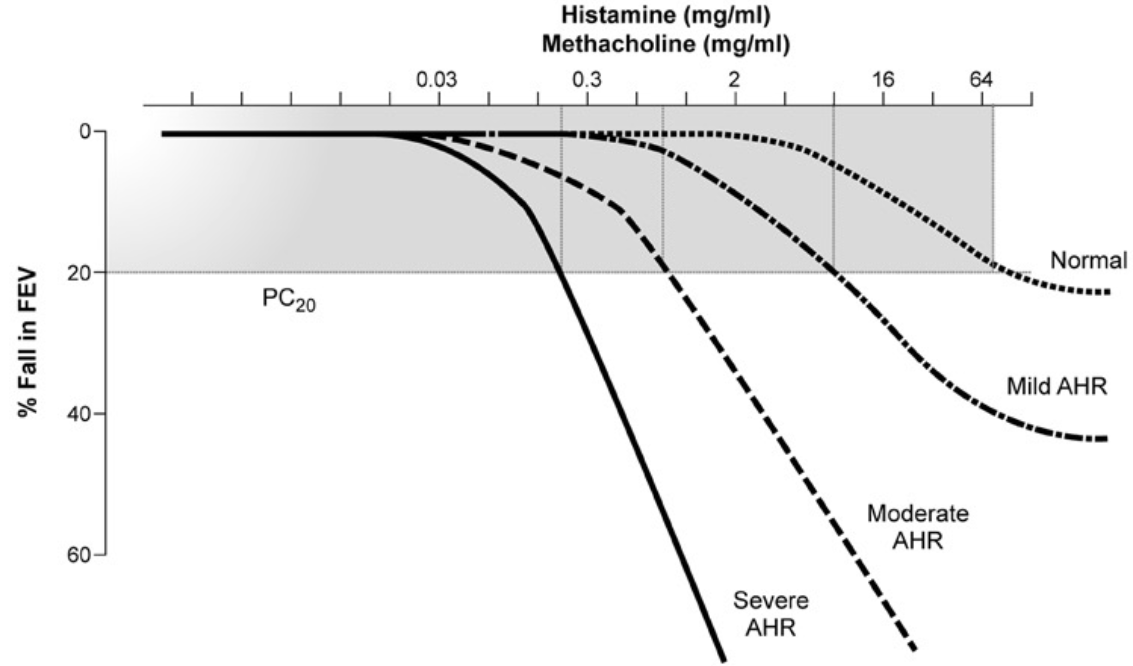

Airway Hyperresponsiveness

- Measured by bronchoprovocation testing

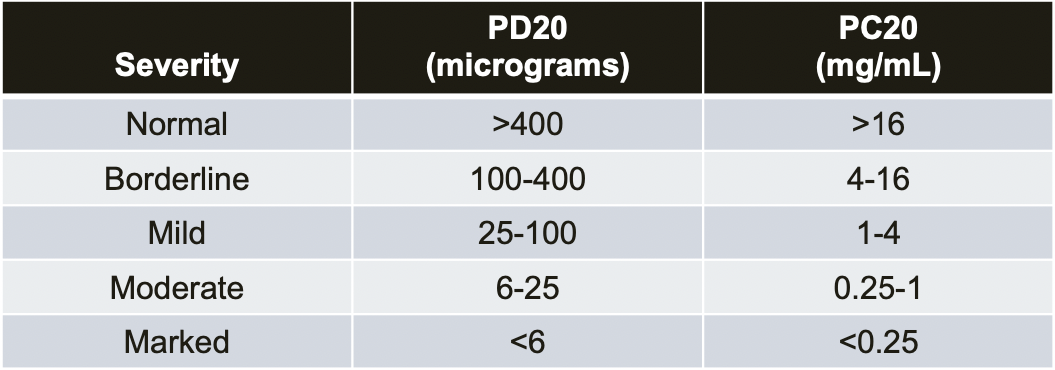

Direct Bronchial Challenge Testing

- Methacholine or Histamine Challenge -- Fall in FEV₁ ≥ 20%

- 2017 ERS Update (Coates AL et al. ERJ 2017;49:1601526)

- Procedures and devices for nebulizing methacholine are not standardized

- PD20 compares better than PC20 between devices (dosage vs concentration)

- 2017 ERS Update (Coates AL et al. ERJ 2017;49:1601526)

Indirect Bronchial Challenge Testing

- Three mechanisms

- Increase in osmolarity of the airway surface → mast cells or basophil mediator release

- Exercise Challenge -- Fall in FEV₁ >10% and 200 mL from baseline

- Mannitol or Eucapnic Hyperventilation -- Fall in FEV₁ ≥ 15%

- Hypertonic Saline

- Activation of A2b receptors on mast cells

- Adenosine 5'-monophosphate (AMP)

- Direct stimulation of airway sensory nerve endings

- Sufur dioxide

- Bradykinin

- Allergens

- Increase in osmolarity of the airway surface → mast cells or basophil mediator release

- More specific though less sensitive than direct challenge tests for identifying patients with active asthma

- Correlate better with airway inflammation and are more predictive of a response to anti-inflammatory treatments

- The best choice when exercise bronchospasm is the question

- e.g. certification for international athletic competition, armed forces, scuba diving

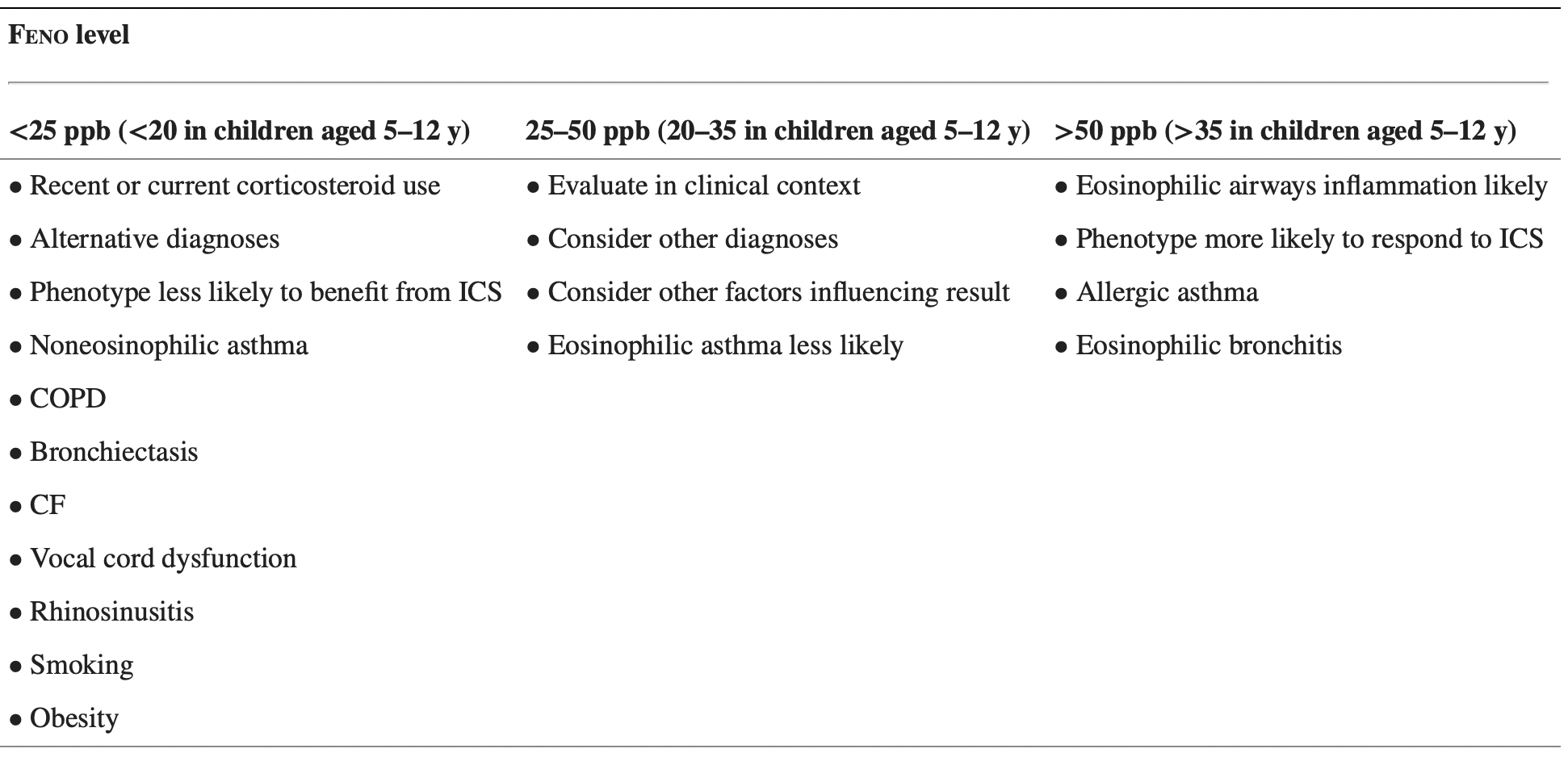

FeNO

- Diagnostic accuracy

- In individuals ≥5 years old for whom the diagnosis of asthma is uncertain using history, clinical findings, clinical course, and spirometry, including bronchodilator responsiveness testing, or in whom spirometry cannot be performed, expert panel recommends the addition of FeNO measurement as an adjunct to the evaluation process

- Interpretations of FeNO test results for asthma diagnosis in nonsmoking individuals not taking corticosteroids

Special Types & Phenotypes of Asthma

Aspirin Exacerbated Respiratory Disease (AERD)

Epidemiology

- Prevalence 7% of adults with asthma

- More common in women

Pathogenesis

- Non-IgE mediated

- "Pseudo-allergic"

Clinical Features

- Asthma + Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP)

- Can take years for all three components to develop

- Chronic Rhinosinusitis usually the first manifestation

- Asthma has a severe and protracted course

- Bronchospasm that occurs (typically 20 minute to 3 hours) after ingestion of aspirin/NSAIDs

- Angioedema and GI symptoms may occur

- Elevated blood eosinophils

- Strong association with HLADPB1-0301

Diagnosis

- Usually made by history

- Aspirin challenge for definitive diagnosis

Management

- Same as for asthma without AERD

- Except consider early use of leukotriene modifiers and avoid NSAIDs

- Emerging role of biologics

- ASA desensitization indicated if worsening sinonasal symptoms despite maximal therapy or treatment of other condition requiring ASA or NSAIDs

- Patients must continue daily aspirin therapy after completing desensitization

- Improved nasal symptoms and decreased regrowth of nasal polyps

- Improved asthma control

- Patients must continue daily aspirin therapy after completing desensitization

Exercise-Induced Asthma (EIA)

Pathogenesis

- Triggered by inhalation of large volumes of relatively cool dry air during vigorous exercise

- heat movement from airway wall → cooling and drying of airway → bronchoconstriction

- exercising involves high minute ventilation (large lung volumes and increased RR) of cool and dry air

Clinical Features

- Symptoms occur after the end of exercise or during prolonged exercise

- Initial bronchodilation followed by bronchoconstriction that peaks 10 to 15 minutes after exercise

- Symptoms resolve after 60 minutes of exercise

- bronchoconstriction is followed by a refractory period (last <4 hours) — release of inhibitory prostoglandins protect against bronchoconstriction even if exercise is continued

- Differentiate from deconditioning — shortness of breath resolves within 5 min after stopping exercise

Diagnosis

- Exercise Challenge Test

- 15% decrease in FEV₁ suggests EIA

- do not do exercise challenge testing in those with existing asthma with typical symptoms after exercise

Management

- Goal is to maintain ability to exercise

- Improve CV fitness → reduce minute ventilation required for given level of exercise → reduce stimulus for bronchoconstriction

- Regular controller treatment with ICS significantly reduces EIA

- Training and sufficient warm-up reduce the incidence and severity of EIA

- Pre-treatment with short-acting bronchodilators (alone or combination)

- Chromoglycates, ICS +/- LABA, Leukotriene modifiers

- If refractory EIA — ICS +/- LABA taken daily regardless of exercise or antileukotriene agents taken daily regardless of exercise

- Diet — rich in omega 3 fatty acids may be helpful

- Breakthrough — indicates poorly controlled asthma → step up treatment after checking technique

Eosinophilic Th2-High Asthma

Cough Variant Asthma & Other Special Types

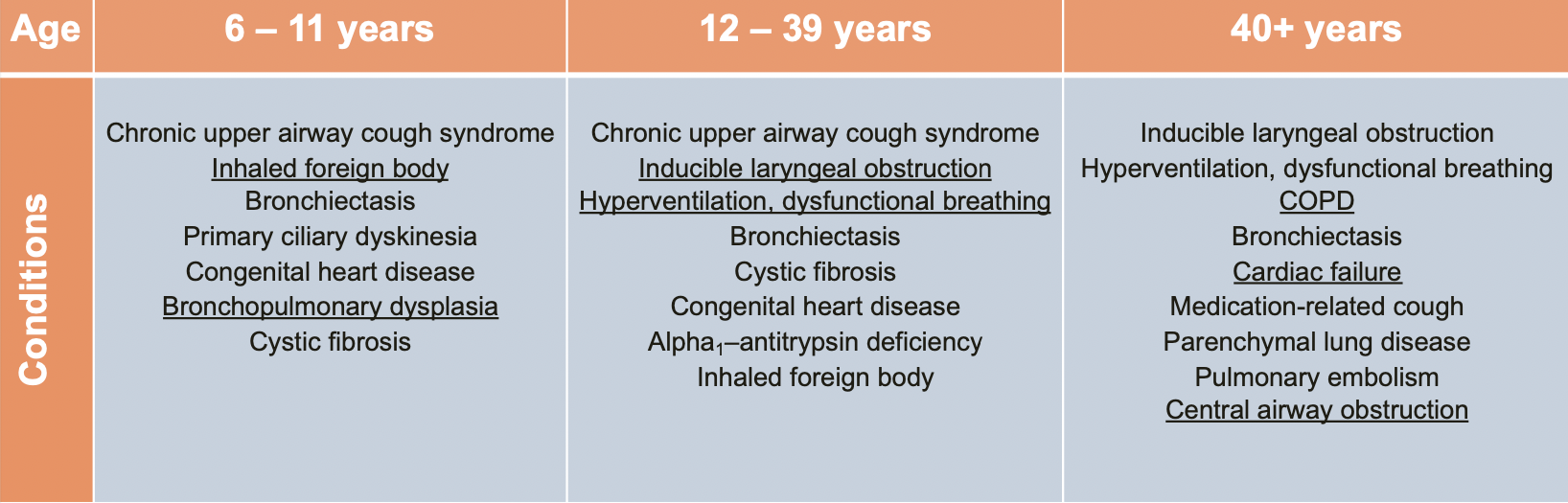

Asthma Mimics

Misdiagnosis of Asthma is Common

- ~30% of adults with "physician diagnosed asthma" may not have asthma

- Aaron SD, et al. JAMA. 2017; 317(3):269

Paradoxical Vocal Fold Motion Asthma (Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction)

Genetic

Cystic Fibrosis

α-1 Antitrypsin Disease

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

Non-Genetic

Hypereosinophilic Loffler's Syndrome & Other Parasitic Infections

Infiltrative Airway Processes

Granulomatous

Amyloidosis

Others

Heart Failure

Central Airway Obstruction

Diseases Associated with Asthma

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis and Fungosis

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

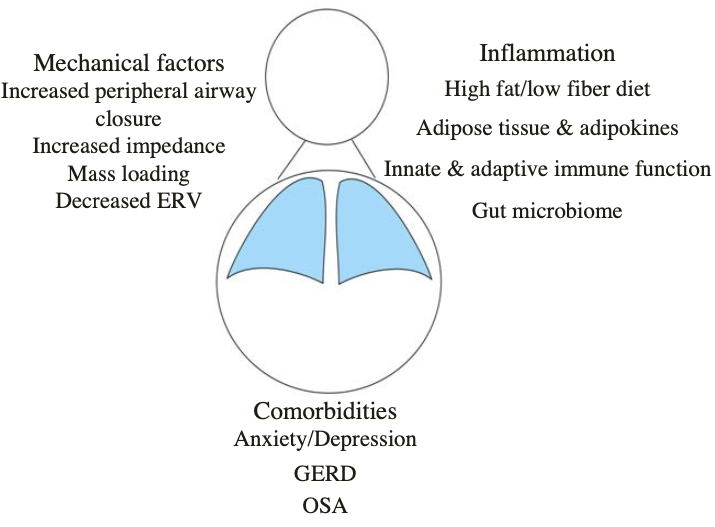

Obesity

- Associated with

- worse asthma control

- higher health care utilization

- poor response to standard controller therapy

- Weight loss is effective (dietary or surgical)

- Recent studies support a role for exercise

- Diet quality

- high protein/low glycemic index, plant-based, Mediterranean

(Dixon AE. AJRCCM 2016)

(Dixon AE. AJRCCM 2016)

Work-Related Asthma

GERD & Asthma

Exacerbation

Risk Factors for Fatal Asthma Attack

- Asthma history:

- History of severe exacerbation requiring intubation and/or ICU monitoring

- History of an exacerbation requiring hospitalization in the previous year

- History of ≥ 3 exacerbations requiring emergency care in the previous year

- Decrease in peak flow to <50% of patient's baseline

- Noncompliance:

- Noncompliant with medication use, including inhaled steroids

- Noncompliant with asthma action plan and regular follow-up

- Medication dependence:

- Requiring >1 canister of rescue therapy per month

- Dependent on systemic steroids

- Patient factors/demographics

- History of IVDU and/or active smoking

- Comorbid psychological disorder

- Poor symptom perception

- Presence of other CV and pulmonary co-morbid conditions

- Low socioeconomic status

- Non-white

- Aspirin sensitivity

- Continued trigger exposure

Detecting the Onset of an Exacerbation

Symptoms

- Progressively worsening breathlessness, wheezing, cough, and chest tightness

- Decreased exercise tolerance and fatigue

Peak Expiratory Flow Measurement

- Baseline peak flow should be estbalished in every patient

- Decrease in peak flow of >20% from normal, or from the patient's personal best value, serves as a marker to detect the onset of an acute exacerbation

- Particularly usefyul in patients who have poor symptom perception

- Upon detection of an acute exacerbation, patients should implement their asthma action plan

Management

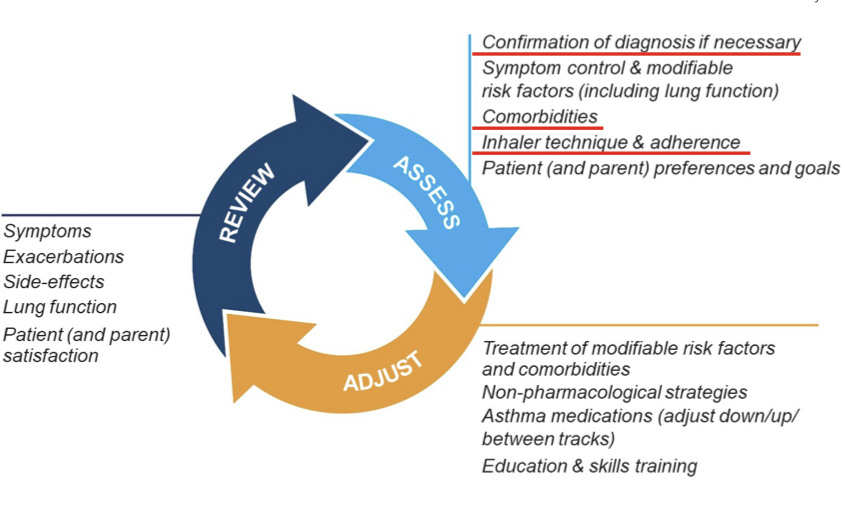

Assessment of Asthma

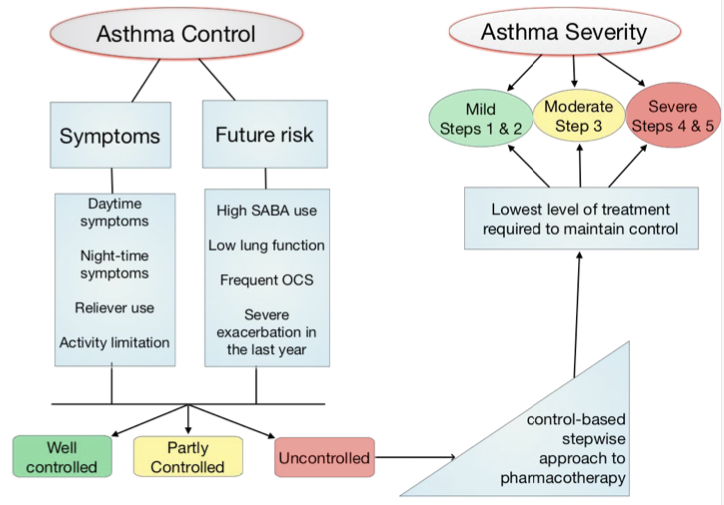

General

- Asthma control

- The level of asthma control is the extent to which the features of asthma can be observed in the patient, or have been reduced or removed by treatment

- Asthma control is assessed in two domains: symptom control and future risk of adverse outcomes

- Poor symptom control is burdensome to patients and increases risk of exacerbations

- Good symptom control can still have severe exacerbations

- Asthma severity

- The current definition of asthma severity is based on retrospective assessment, after at least 2-3 months of controller treatment, from the treatment required to control symptoms and exacerbations

- This definition is clinically useful for severe asthma as it identifies patients whose asthma is relatively refractory to conventional high dose ICS-LABA and who may benifit from additional treatment such as biologic therapy

- Clinical utility of the term 'mild asthma' is unclear

- In particular, the term is often used in clinical practice to mean infrequent or mild symptoms and patients often incorrectly assume that it means they are not at risk and do not need controller treatment

- Therefore avoid the term mild asthma

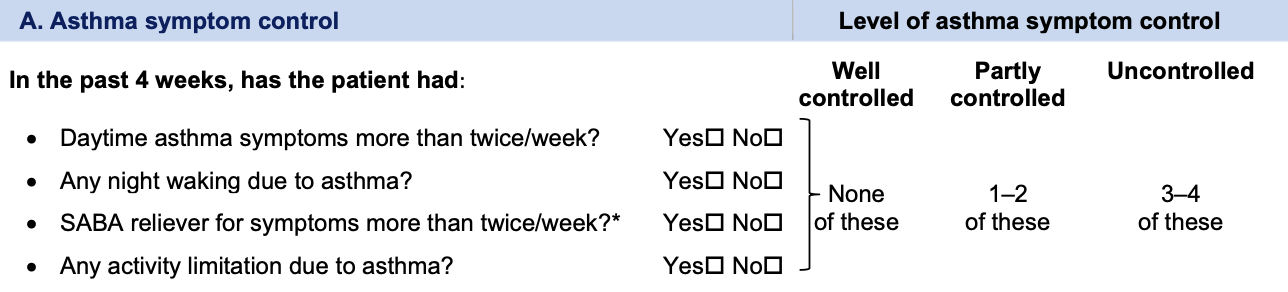

Step 1: Assess Asthma Control

- Step 1A: Assess symptom control over the last 4 weeks

- can also use symptom control tools such as the Asthma APGAR tool

- Level of asthma control is the degree to which therapeutic interventions minimize the manifestations of asthma in terms of impairment and risk

-

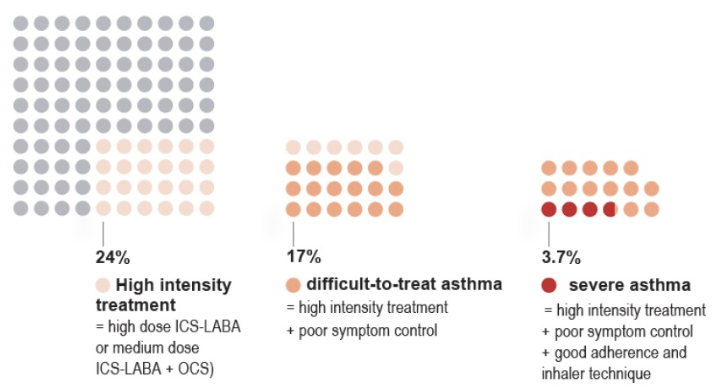

Assessing Asthma Severity

- The currently accepted definition of asthma severity is based on 'difficulty to treat'

- Severity should be assessed retrospectively from the level of treatment required to control the patient's symptoms and exacerbations i.e. after at least several months of treatment

-

Severe Asthma

- Asthma that remains uncontrolled despite optimized treatment with high dose ICS-LABA, or that requires high dose ICS-LABA to prevent it from becoming uncontrolled

- Distinguish severe asthma from difficult to treat due to inadequate or inappropriate treatment or persistent problems with adherence or comorbidities (chronic rhinosinusitis or obesity)

- Treatments defer

- Those with difficult to treat can become well-controlled if those issues are addressed

- Khurana & Jarjour. Clin Chest Med. 2019 Mar;40(1):59

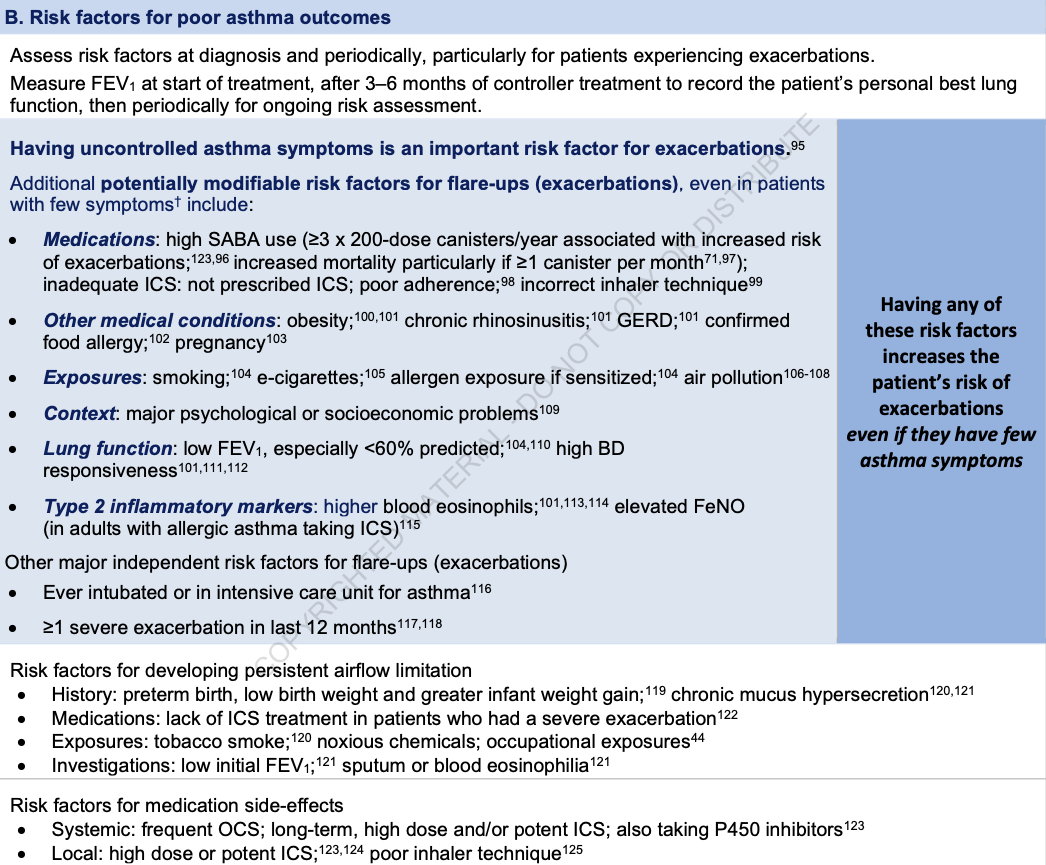

- Step 1B: Identify any other risk factors for exacerbations, persistent airflow limitation or side-effects

- Step 1C: Measure lung function at diagnosis/start of treatment, 3-6 months after starting controller treatment, then periodically, e.g. at least once every 1-2 years, but more often in at-risk patients and those with severe asthma

- Lung function does not correlate strongly with asthma symptoms in adults

- Low FEV₁ is a strong independent predictor of risk of exacerbations even after adjustment for symptom frequency

- Also a risk factor for lung function decline, independent of symptom levels

- A normal or near normal FEV₁ in a patient with frequent respiratory symptoms prompts the consideration of alternative causes for the symptoms -- cardiac disease, cough due to post nasal drip, GERD

- Persistent bronchodilator responsiveness

- Finding significant bronchodilator responsiveness (increase in FEV₁ >12% and >200 mL from baseline) in a patient taking controller treatment or who has taken a SABA within 4 hours, or a LABA within 12 hours (or 24 hours for a once-daily LABA), suggests uncontrolled asthma

- Interpreting changes in lung function in clinical practice

- With regular ICS treatment, FEV₁ starts to improve within days and reaches a plateau after around 2 months

- Document the patients highest FEV₁ reading -- more useful for comparison than FEV₁ % predicted

- Some patients may have a faster than average decrease in lung function, and develop persistent (incompletely reversible) airflow limitation

- While a trial of higher dose ICS-LABA and/or systemic corticosteroids may be appropriate to see if FEV₁ can be improved, high doses should not be continued if there is no response

- With regular ICS treatment, FEV₁ starts to improve within days and reaches a plateau after around 2 months

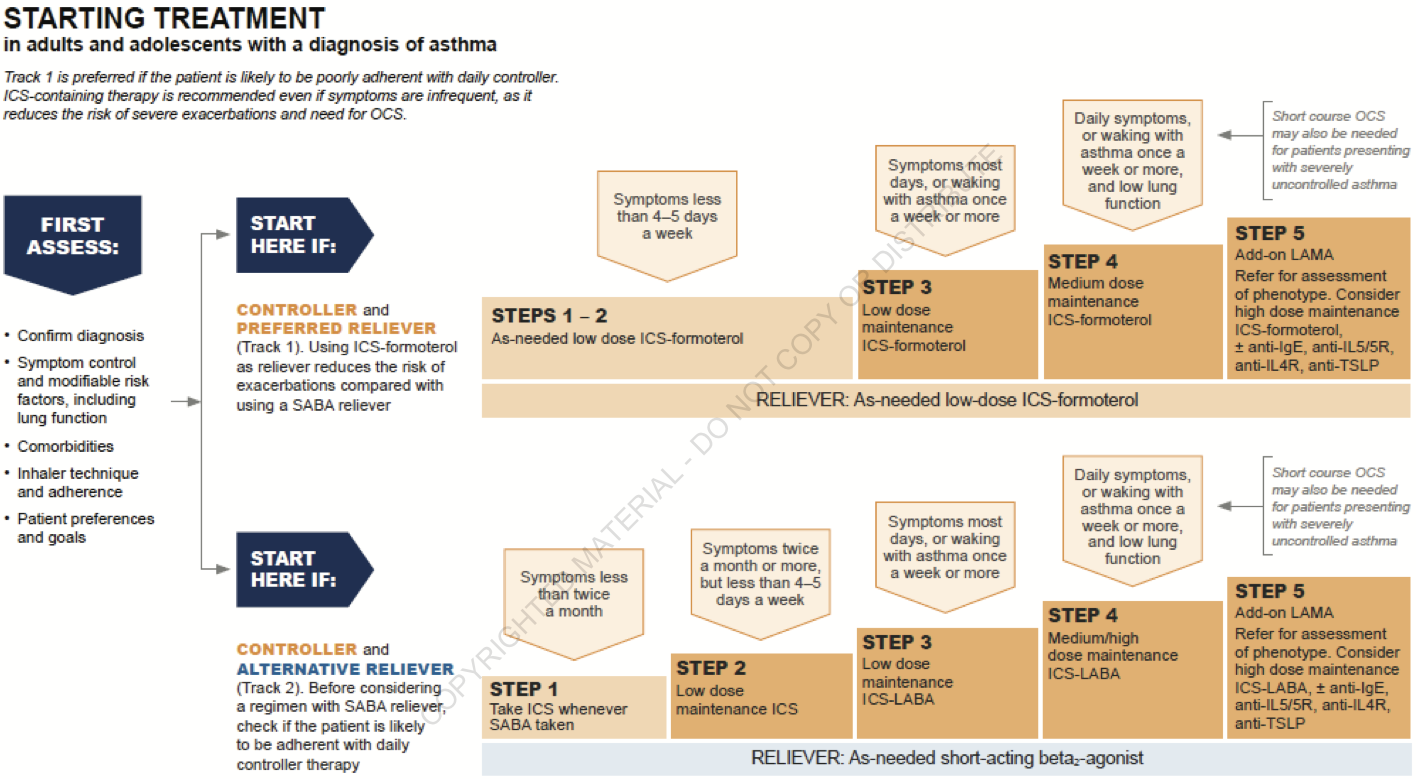

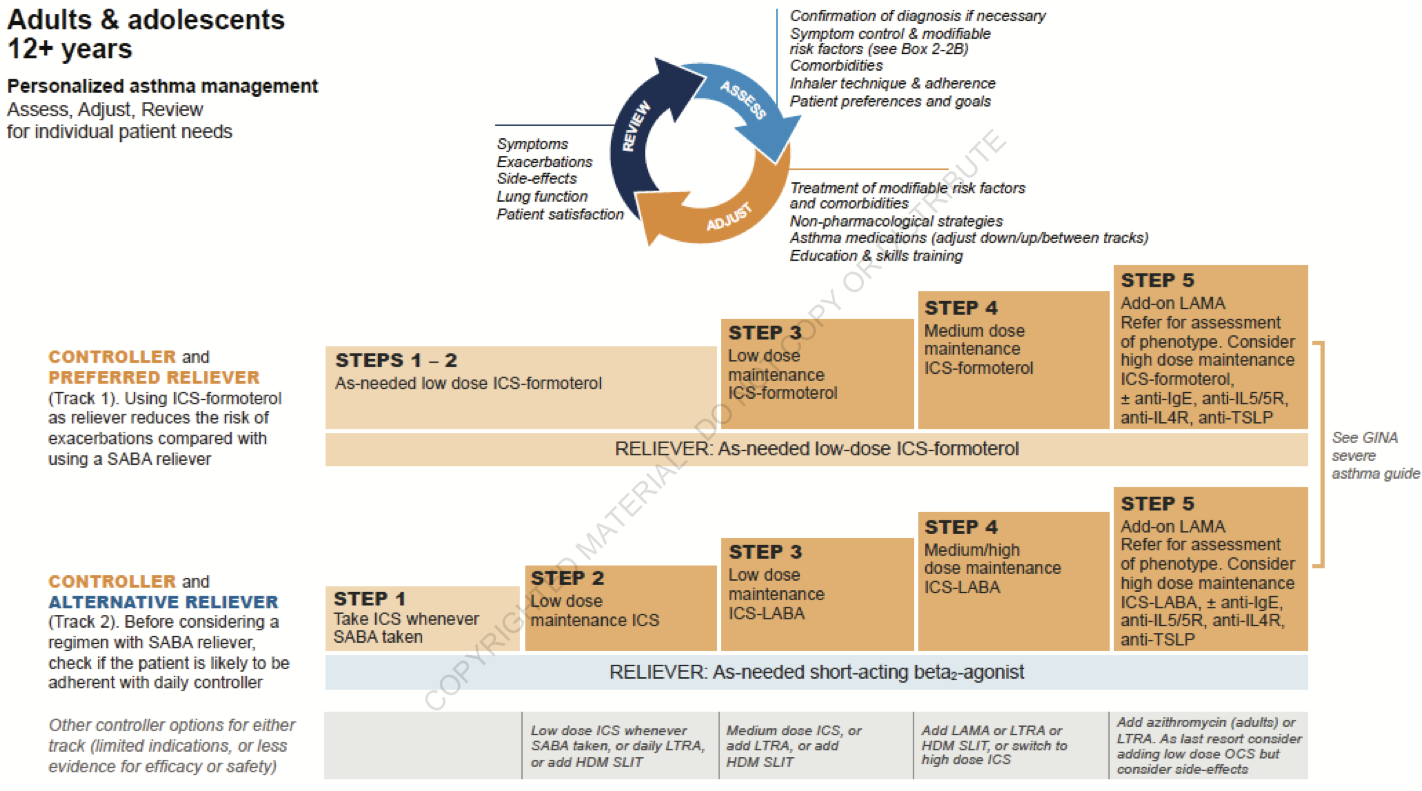

Step 2: Assess Treatment Issues

- Step 2A: Document patient's current treatment step/initial treatment step

- Both domains of asthma control (symptom control and future risk) should be taken into account when choosing asthma treatment and reviewing the response

- GINA no longer recommends treatment of asthma in adults and adolescents with SABA alone

-

Starting Treatment

-

Adjusting Treatment

- Rationale & Evidence for as-needed ICS/formoterol

- Patients use their inhaler when they have symptoms

- Adherence to scheduled ICS is poor

- SABA overuse is a/w increased risk of death

- Even people with mild asthma have exacerbations

- SYGMA 1&2, Novel START, PRACTICAL

- 4 12-month studies, ~10000 patients

- As-needed ICS/formoterol decreased severe exacerbations vs SABA

- As-needed ICS/formoterol similar to scheduled ICS

- Much lower steroid exposure

-

NAEPP EPR4 Focused Update

- FeNO

- Allergen mitigation

-

ICS

- ICS for Persistent Asthma

- Large body of evidence shows that ICS use in asthma

- reduces risk of severe exacerbations and hospitalization

- reduces mortality

- improves symptoms and quality of life

- reduces exercise induced bronchoconstriction

- improves lung function

- slow the deterioration of lung function

- may prevent airway remodeling

- Large body of evidence shows that ICS use in asthma

- ICS + LABA for Asthma

- Adding LABA to low dose ICS (in a combination inhaler) provides

- additional improvement in symptoms

- additional improvement in lung function

- decrease in risk of exacerbations

- small reduction in reliever use

- Addition of LABA to low dose ICS was more effective than increase in ICS dose alone

- LABA should never be used as monotherapy in asthma

- Adding LABA to low dose ICS (in a combination inhaler) provides

- ICS for Persistent Asthma

-

LAMA

- Tiotropium soft mist inhaler is the only LAMA that is FDA approved for asthma

- As add-on therapy to ICS

- Improved lung function; reduced exacerbations

- LABA still preferred over LAMA for add-on therapy to ICS

- As add-on therapy to ICS + LABA

- Improved lung function

- Improved asthma control

- Increased time to first exacerbation

- Not recommended as monotherapy

-

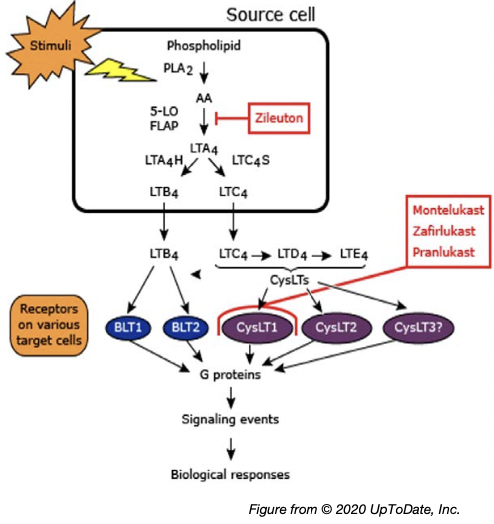

Leukotriene Modifiers in Asthma

- Efficacy (vs placebo)

- reduced risk of exacerbations

- improve lung function

- improve symptoms and QOL

- reduce need for rescue SABA

- Effects are variable and generally less than with ICS

- Less effective than LABA as add-on therapy to ICS in improving exacerbations and lung function

- Greater response in AERD and EIB

- Efficacy (vs placebo)

-

Immunotherapy

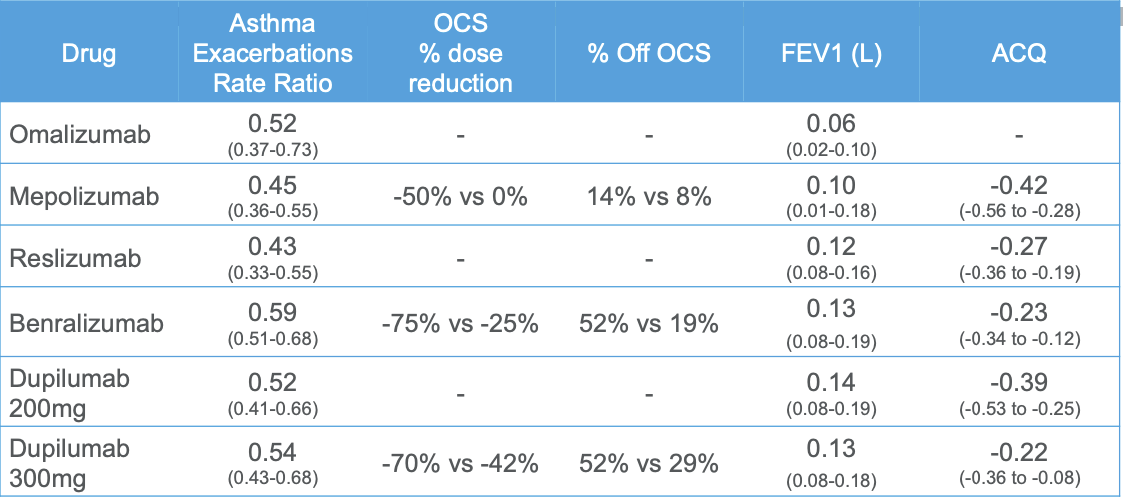

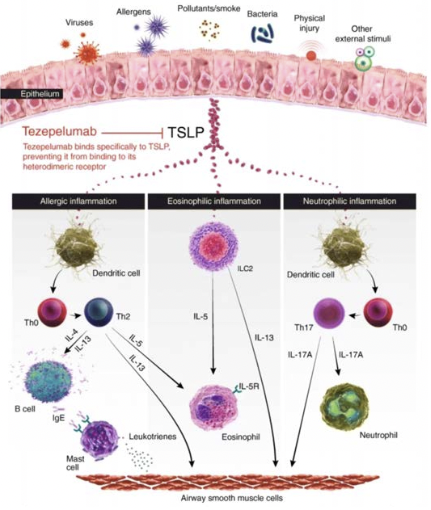

- Efficacy of Biologics

-

Omalizumab

- Anti-IgE humanized monoclonal antibody

- Binds to free circulating IgE at the same site as high-affinity IgE receptor

- Indication

- Moderate - severe allergic asthma

- Serum IgE 30-700 IU/mL with sensitivity to >1 perennial allergen

- Adverse Effects

- Small risk of delayed anaphylactic reactions (0.2%)

- Administration: subcutaneous injections every 2-4 weeks

-

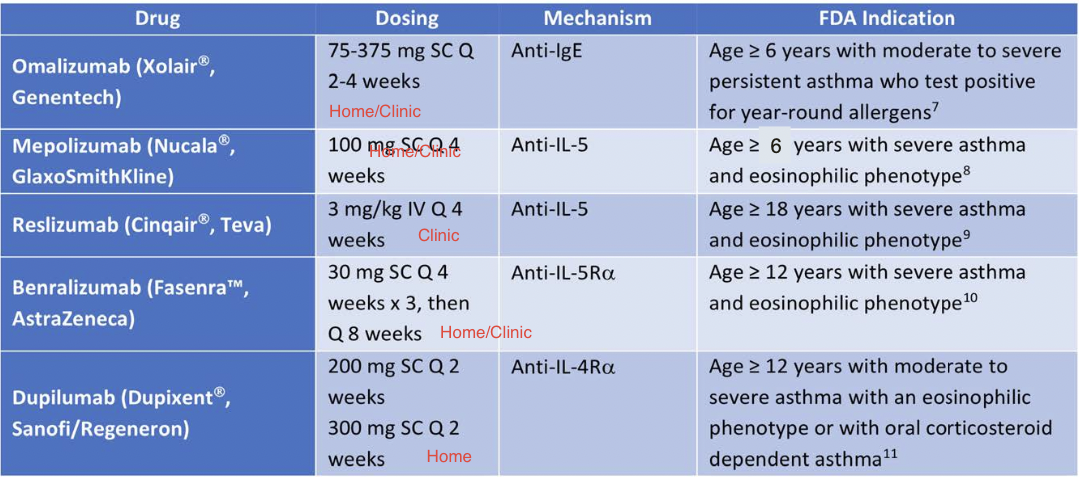

Anti-IL5 Therapy

- Anti-IL5 monoclonal antibodies -- mepolizumab, reslizumab

- Anti-IL5 receptor monoclonal antibody -- benralizumab

- Indication:

- Add-on maintenance therapy for patients with severe asthma with an eosinophilic phenotype

- Administration:

- Mepolizumab -- 100 mg subcutaneous injection every 4 weeks

- Reslizumab -- weight-based IV infusion every 4 weeks

- Benralizumab -- 30 mg subcutaneous every 4 weeks x 3, then every 8 weeks

-

Dupilumab

- Anti-IL4Rα human monoclonal antibody

- Binds to α subunit of IL-4 receptor

- Inhibits the activity of both IL-4 and IL-13

- Indication:

- Moderate-to-severe, eosinophilic asthma and OCS-dependent asthma

- Dose:

- 400 mg or 600 mg initial loading dose, then 200 mg or 300 mg every 2 weeks subcutaneously

- Higher dose in OCS-dependent asthma or comorbid atopic dermatitis

-

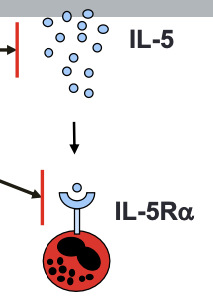

Tezepelumab

- Anti-TSLP antibody

- Binds specifically to TSLP preventing it from binding to its heterodimeric receptor

- Menzies-Gow et al. Respir Res 2020 Menzies-Gow et al. NEJM 2021

-

Macrolides

- Azithromycin in asthma (AMAZES) (Gibson, Peter G et al. The Lancet 2017)

- Taken 500 mg thrice weekly improved percentage of exacerbation free days

- Azithromycin in asthma (AMAZES) (Gibson, Peter G et al. The Lancet 2017)

-

Bronchial Thermoplasty

- Uses radiofrequency to the proximal airways to ablate smooth muscle thereby decreasing the ability of smooth muscle to constrict → decreased airway resistance → decreased airway hyperresponsiveness

- Performed with a flexible bronchoscopy in three separate procedures — cannot do this to RML (due to size?)

- FDA approved for >18 yo w/ severe and persistent asthma not well-controlled with ICS and LABA

- Current recommendations are that this only be done in adults with severe asthma only in the contexts of IRB-approved, independent, systemic registry or a clinical study due to consequences/adverse events → increased airway secretions and URIs

- Relative contraindications — patients who have received oral corticosteroids at least 4 times in the preceding 5 years or who were not considered to have been receiving a stable maintenance pharmacologic regimen

- Don’t do during exacerbation of asthma

- AIR2 Trial (Castro M, et al, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 81 : 116)

- Improvement in Asthma QOL

- Reduction in healthcare utilization

-

Treatment of Non-Type 2 (Th2 Low) Asthma

- 40-50% of asthma patients do not have Type 2 inflammation

- Severe, uncontrolled asthma without evidence for Type 2 inflammation referred to as Type 2 Low Asthma or Non-Type 2 Asthma

- Potential targets for Type 2 Low Asthma:

- Macrolide antibiotics

- Bronchial thermoplasty

- Step 2B: Watch inhaler technique, assess adherence and side effects -- Assess, Adjust, Review Response

- Step 2C: Check that the patient has a written asthma action plan

- Step 2D: Ask about the patient's attitudes and goals for their asthma and medications

Step 3: Assess Comorbidities

- Rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, GERD, obesity, OSA, depression & anxiety can contribute to symptoms and poor QOL and sometimes poor asthma control

-

- Difficult Asthma; # All asthma

-

GERD & Asthma

- Prevalence 32-84% by esophageal pH monitoring studies; about half are asymptomatic

- carefully review symptoms: heartburn, regurgitation, water brash, dysphagia, sore throat, choking, hoarseness, dental erosions, chest pain, cervical pain, worsened asthma symptoms with eating, alcohol, supine position, theophylline

- Proposed mechanisms -- 'Reflux' vs 'Reflex'

- Likely a bi-directional relationship

- Studies demonstrate some benefit in symptomatic GERD and uncontrolled asthma

- Improvement in peak flow, QOL, exacerbations

Chronic Rhinosinusitis & Asthma

- Symptomatic inflammation of the paranasal sinuses and the nasal cavity

- Chronic Rhinosinusitis -- lasting > 12 weeks

- with or without nasal polyps (CRSwNP or CRSsNP)

- The unified airway model

- Links the upper and lower airway as a single functional group

- Shared systemic inflammatory pathways

- Prevalence of CRS

- 10-12% in general population

- 23.4-74% in all asthma

- 84% in severe asthma

- Associated with decreased lung function, QOL, severe exacerbations

Paradoxical Vocal Fold Motion & Asthma

- Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD)/Inspiratory Laryngeal Obstruction (ILO)

- Laryngeal hypersensitivity

- Occurs commonly as asthma mimic and comorbidity

- Prevalence

- 19% in all asthma

- 32% in difficult asthma

- Clinical suspicion and detailed history

- Triggers, rapid onset/offset, phase of respiration affected, other laryngeal symptoms

- Objective confirmation often elusive

- Questionnaire screening, laryngoscopy, challenge tests

- Respiratory retraining, laryngeal hygiene, treat LPRD (laryngopharyngeal reflux disease)

Obesity & Asthma

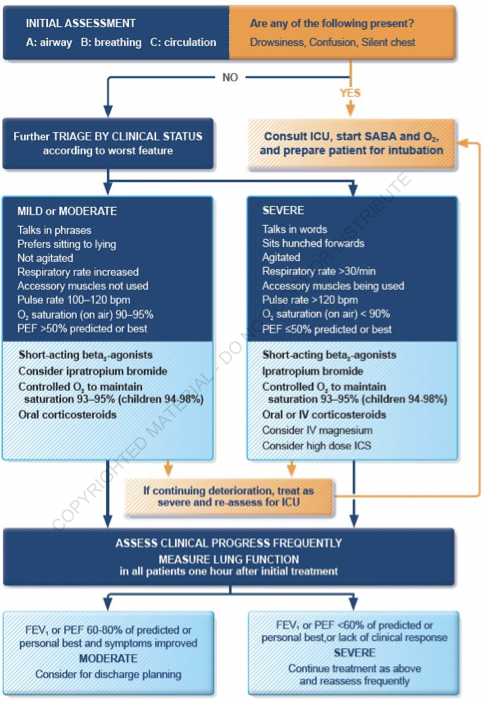

Management of Asthma Exacerbation

Indicators of Severity

Clinical Findings

- Severe Exacerbation

- The presence of tachypnea, tachycardia, use of accessory muscles of inspiration, diaphoresis, inability to speak full phrases, inability to lie supine due to breathlessness, and pulsus paradoxus

- Findings can be present alone or in combination

- These findings lack sensitivity and might be absent in patients with severe obstruction

Peak Expiratory Flow Measurements

- Best method for objective assessment of severity

- Values <200 L/min or <50% of patient's baseline are indicative of severe attack

- Also used to monitor response to therapy and a predictive marker for the presence of hypercapnia; a decrease in PEF to <25% of patient's baseline is an indirect marker for the presence of hypercapnia

ABG Analysis

- Not routinely required, considered in patients with PEF or FEV₁ <50% predicted or for those who do not respond to initial treatment or are deteriorating

- Severe Exacerbation

- Marked hypoxia (PaO₂ <60 mm Hg or SpO2 <90%)

- Normal or High PaCO₂ = severe airway obstruction

- hyperventilation should lead to a decreased PaCO₂

- worsening hypercapnia or normocapnia is an indication for intubation

Imaging

- Chest x-ray not routinely recommended

- Presence of hyperinflation is a sign of severe obstruction and air trapping

Treatment

Systemic Glucocorticoids

- Essential for exacerbations refractory to intensive bronchodilator therapy

- Indications for early administration of systemic glucocorticoids (within 1 hour)

- PEFR <40% of patient's baseline → immediate administration

- PEFR >40% but <70% of patient's baseline → early administration

- Lack of improvement in PEFR after several treatments with rapid-acting bronchodilators

- Those on systemic steroid therapy and still have an exacerbation → higher dose than baseline needed

- Onset of action

- 4-6 hours after administration

- Optimal dose

- Daily doses of OCS equivalent to 50 mg prednisolone as a single morning dose, or 200 mg hydrocortisone in divided doses

- Route

- Oral = IV

- Oral preferred because it is quicker, less invasive and less expensive

- Duration

- 5-7 days (just as effective as 10 to 14 day courses)

Inhaled Corticosteroids

- High dose ICS given within the first hour after presentation reduces the need for hospitalization in patients not receiving systemic corticosteroids

- When added to systemic corticosteroids, evidence is conflicting

Indications for Hospitalization in Acute Asthma Exacerbation

- No improvement after 4-6 hours off aggressive management with inhaled bronchodilators and systemic glucocorticoids

- Hemodynamic instability, persistent hypoxemia, hypercarbia, wheezing, presence of concomitant pneumonia, CHF, and other comorbid conditions

- Presence of risk factors for fatal asthma attack

Airway Management in Acute Asthma Exacerbation

- Indications for Intubation

- Decrease in RR

- AMS

- Failure to maintain respiratory effort

- Worsening acidosis and hypercapnia

- Hypoxia with O₂ saturation <95% in the presence of high-flow supplemental oxygen

- Ventilation settings

- Goal is to adequately oxygenate and ventilate while minimizing airway pressures

- Severe bronchoconstriction reduces airflow during expiration; the ventilator settings should provide adequate time for expiration

- Achieved by using high inspiratory flow rates (80-100 L/min), low tidal volumes, and low respiratory rates (10-14 breaths/min) (latter = best at reducing Auto-PEEP)

Asthma in Pregnancy

Perioperative Care

Complications of Care

Backlinks

- 01.1. Obstructive Lung Diseases

- 02.2. Eosinophilic Lung Diseases

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure

- 10.3. Airway Diseases in Critical Care